How a liberal Santa Monica high school produced a top Trump advisor and speechwriter

An unlikely story.

Too-cool-for-school upper-class students at Santa Monica High scoffed when administrators in 2002 reinstated a daily recitation of the pledge of allegiance.

Most students in the liberal enclave slouched in their chairs and chatted over the morning ritual, which was widely viewed as a throwback to an American patriotism that seemed outdated in the multicultural mash-up of L.A.’s Westside.

Not Stephen Miller. Every day, the student body’s best-known and least-liked conservative activist stood at his desk, put his hand over his heart and declared his love of country.

That solitary rebellion of conventionalism was an affront to the left-leaning sensitivities of many on the campus, making him a nerd to some, a provocateur to others.

Now Miller’s brand of brash conservatism, fostered during those years at Santa Monica High, is helping to shape the next presidency.

How the People’s Republic of Santa Monica, as the city is sometimes jokingly called, gave rise to the skinny-suited man now at Donald Trump’s side is as much a story about one teen’s intellectual tenacity as it is about the backlash to liberalism at the turn of the millennium.

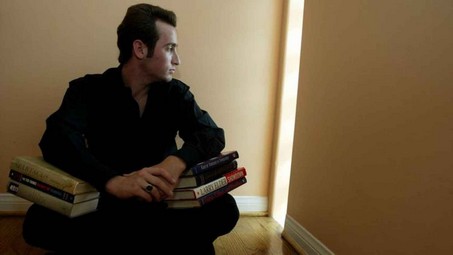

The culturally sensitive environment at Samohi infuriated and ultimately shaped Miller, 31, now a senior advisor to Trump who is helping to draft this week’s inaugural address and will have a coveted West Wing office.

As he was finding his voice at Santa Monica High, Miller bemoaned the school’s Spanish-language announcements, the colorful festivals of minority cultures, and the decline, as he saw it, of a more traditional version of American education.

Yet that robust progressive tradition nurtured Miller’s rise, teaching him how to fight for his beliefs, even if it meant he had to stand alone, in his tennis shorts and polo shirts, as he often did.

“These challenges were some of the toughest I faced in life,” Miller said in an interview. “When we think of nonconformity, we tend to imagine kids in the ’60s rebelling against ‘the system.’ This was my system. My establishment was a dogmatic educational system that often uniformly expressed a single point of view.”

After graduating, Miller went on to Duke University and found himself on the far right of the GOP. He landed a job on Capitol Hill with then-Rep. Michele Bachmann of Minnesota and later with Sen. Jeff Sessions, the Alabama conservative and next likely attorney general who relied on the young conservative to help him defeat immigration reform in 2013. Miller also came into the orbit of Breitbart News’ Stephen Bannon and eventually Trump’s campaign, for which Miller became a trusted advisor and often served as a warm-up act at big rallies.

Hard-right conservatives praise Miller as a future leader, but liberals and moderates deride what they see as hateful, divisive rhetoric, an abrasive way of belittling opponents and a dismissal of the struggles of minorities.

It was the picturesque campus blocks from the Pacific Ocean where Miller engaged in his first political battles: in the classroom, where teachers didn’t know what to do with him; at the school newspaper, where he wrote an op-ed, “A Time to Kill,” supporting the Iraq War; at district offices, where he tangled with administrators.

Oscar de la Torre, a former counselor and now school board member who sparred publicly with the young student, recalled the frustrations of working with the teenage Miller on a district committee that was scrutinizing the community fundraising imbalance between wealthier and poorer campuses.

“Early on in life, he was on a crusade against liberalism and liberals,” said De La Torre, who grew up in Santa Monica’s historically Latino and African American Pico neighborhood and graduated a decade before Miller. “He just didn’t buy it. He didn’t believe the oppression existed.… This guy is 17 years old, and it’s like listening to someone who’s 70 years old — in the 1930s.”

Santa Monica was experiencing growing pains as Miller came of age at the start of the 21st century. The city was transforming from a laid-back coastal community of rundown rent-controlled apartments into an upscale celebrity and tourist mecca. But it still suffered from entrenched working-class poverty and on-again, off-again gang violence.

Samohi, the city’s biggest public high school, served as a laboratory for addressing the clash between cultures and rising income inequality.

These were the late 1990s, the years immediately after a mostly white jury acquitted Los Angeles police officers in the beating of motorist Rodney King, sparking days of civil unrest; when Latino students staged walkouts to protest Proposition 187, a California ballot measure that would have prohibited children who illegally immigrated from going to public schools or receiving government-paid medical care.

Miller grew up in the tony north-of-Montana neighborhood, the middle child, in a Jewish family of longtime Franklin Roosevelt Democrats. He played tennis and golf. But their status abruptly shifted when his parents’ real estate company faltered and the family moved to a rental on the south side of town.

A subscription to Guns and Ammo magazine introduced him to the writings of National Rifle Assn. leader Wayne LaPierre, sparking Miller’s interest in politics. The conservative ideas were like nothing he had ever heard.

By the time Miller began his freshman year in 1999, minority students were the majority on campus, and the community was engulfed in conversations about race and class. The district was working to improve the educational outcomes for all students, not just the wealthier graduates scooped up by Stanford University and UC Berkeley, in part by emphasizing an inclusiveness that has become a mainstay at schools elsewhere today.

Then 9/11 hit, and as Miller watched Samohi respond to the 2001 terrorist attacks — he says teachers and administrators openly opposed the Iraq war and mocked then-President George W. Bush — he “resolved to challenge the campus indoctrination machine,” he wrote in Frontpage Magazine, a publication from David Horowitz, the 1960s Marxist-turned-conservative author.

“During that dreadful time of national tragedy, anti-Americanism had spread all over the school like a rash,” the 17-year-old Miller wrote in “How I Changed my Left-Wing High School,” soon after graduation. “I decided to become involved.”

Miller contacted radio show host Larry Elder, the conservative African American commentator, becoming a regular guest and attacking the liberal bias he says he felt at school. He welcomed Horowitz to speak on campus, sparking resistance, as he tells it, from the administration.

And he began to garner his first national audience as conservative listeners from around the country called or faxed complaints to the school, much to the dismay of administrators.

“He would take the opposing position and almost shock people. It would send reverberations through the room,” said one acquaintance, granted anonymity to speak frankly about Miller. “He would sort of chuckle and enjoy that.”

Latino students recall Miller telling them dismissively that they would do better to work on their English language skills rather than spend their time forming clubs based on ethnicity. Some called him racist. Others remember Miller giving a speech questioning why students should be required to pick up their trash when janitors were employed for such tasks.

“For many people the things he would say and do were offensive heresies,” said Ari Rosmarin, former editor of the school newspaper and now a New York attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union. “He loved playing that role, loved drawing people’s outrage, he loved the performance.”

Those days were a dress rehearsal for his time at Duke, where he backed lacrosse players in a racially charged rape case that was eventually dropped, and then in the Trump campaign, where he helped shaped policies, including its stance on illegal immigration.

In a 2002 letter to the editor of a Santa Monica news website, Miller bemoaned “the rampant political correctness” at Samohi, including condom giveaways and Spanish-language announcements that he considered “a crutch … preventing Spanish speakers from standing on their own. As politically correct as this may be, it demeans the immigrant population as incompetent, and makes a mockery of the American ideal of personal accomplishment,” he wrote.

Some of that rhetoric was echoed in the Trump campaign.

“That Stephen Miller would take the playbook he used to provoke Santa Monica High School students and turn into becoming one of the most powerful people in the country, I think that’s something nobody saw coming,” Rosmarin said.

Rep. Julia Brownley (D-Westlake Village), who was the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District’s board president at the time, remembered Miller showing up at events in coat and tie — “unlike any other student” — to argue against special treatment for immigrants and others.

“He had very conservative views — the exact opposite of what we were trying to accomplish in the school district,” she said.

The more opposition he faced, the more Miller dug in. “He was very brave at the time, when you consider the pressures on him,” said Horowitz, who introduced Miller to Sessions.

Miller’s willingness to offend provided an easy punchline for the student paper. For the annual satire issue, the staff crafted a fake letter to the editor from him celebrating the cancellation of club day, when Latinos and other student groups sold ethnic foods. It mockingly said he preferred white bread and Virginia country ham.

But in Miller’s telling of those days, he was trying to unify the campus, by resisting defining students by their differences and instead by their commonality as Americans. He said he advocated for the reinstatement of the pledge of allegiance as part of that.

Kesha Ram, a student activist who led “racial harmony” retreats and often sparred with Miller, said his views, not surprisingly, made him an outsider at a school where multiculturalism was valued and a white male-dominated society was challenged.

“Stephen really did grow up in an environment where he could feel what it was like for white males to feel like the minority,” said Ram, the daughter of an immigrant Pakistani-Hindi father and American-born Jewish mother.

“I think he was one of the first examples we all had of someone who really felt threatened and left out by our celebration of multiculturalism and diversity,” said Ram, a former Vermont state representative who campaigned for Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. “I think it helped him to be a stronger advocate for his position to go to a high school like ours.”