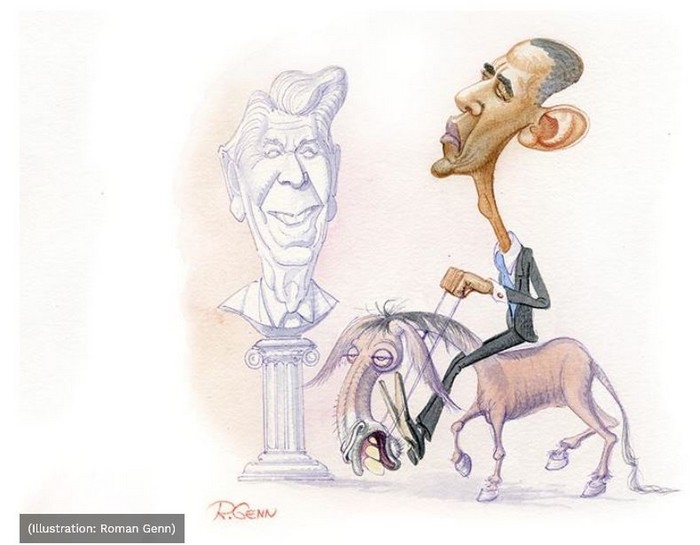

Obama Was Not the Left’s Reagan

The remark signaled Obama’s ambition. He wanted to be the liberal Reagan, or rather the liberal anti-Reagan: the person who pulled American politics back to the left a generation after Reagan pulled it to the right. Bill Clinton had not done that. Instead he had governed in Reagan’s shadow. Obama thought that the time was ripe to emerge from that shadow. Many of his supporters wanted the same thing. For them, “Yes we can” — one of his 2008 campaign slogans — meant “Yes, we can overcome Reaganite conservatism and Clintonite triangulation.”

As late as last April, the commentator Fareed Zakaria was able to write that Obama had pulled it off. “Obama aspired to be a transformational president, like Reagan. At this point, it’s fair to say that he has succeeded.” This judgment was not crazy, but it turns out to have been premature. Less than a year later, it appears that the Obama project has failed.

He did manage to pull his own party to the left. In this respect he was like Reagan. Many pre-Reagan Republicans were less ideologically conservative, and much more inclined to cooperate with Democrats in expanding the welfare state, than Reagan. He defeated such Republicans in the 1980 primaries, and his alliance with them thereafter was often uneasy.

Reagan showed his party that there was a different path to winning elections from running on a lite version of the Great Society. Demographic trends — suburbanization, de-unionization, movement south and west — gave Republicans confidence in this new path. At the end of Reagan’s presidency, one of the Republicans he had beaten in 1980 ran on a basically Reaganite platform to succeed him.

Later Republicans were still more conservative. Reagan drew his party far enough to the right that the compromises with liberalism that he made during his career became unthinkable in the aftermath of his career. He created a Republican party that wouldn’t put up with the kind of tax increases that he had signed.

A year into Obama’s presidency, liberal writer Peter Beinart looked back on the Bill Clinton era as a time when Democrats had lived in fear of America’s latent conservatism. They had to avoid sudden moves that would awake the sleeping bear. That fear had vanished under Obama: “From top to bottom, Democrats have decided to bet the party’s future on the belief that Americans prefer bold liberals to cautious ones.” On criminal justice, on entitlements, on immigration, on abortion, on religious liberty, Democrats staked out positions and adopted rhetoric that were much less moderate than they had previously been. The new Democratic consensus included Hillary Clinton, who ran in 2016 as the heir to Obama rather than to her own husband.

Clinton, indeed, ran a more thoroughgoingly progressive campaign in 2016 than Obama had in 2008. She eschewed the outreach to white Evangelical Christians in which he had engaged. She didn’t talk about finding common ground on abortion, as Obama had and as she herself had in previous political moments. For most of his presidency, Obama had stressed that there were limits to how much he could liberalize policy toward illegal immigrants using his executive authority. Finally he decided he could go far to relax the laws, and in 2016 Clinton said she was prepared to go farther.

Just as the Republicans of an earlier era concluded that they could ride a rising conservatism to power, so Democrats in the Obama years embraced a new political strategy. They thought that changing demographics had displaced the old political order. Christian conservatism was in decline. The white working class was a shrinking share of the population. The bear was finally dead.

For Reagan to succeed in pulling the country to the right, he not only had to convince his party that it was safe and smart to come along with him. The party’s confidence in the new approach also had to be borne out, and be seen to be borne out. And this in turn had to shock the opposition party into assimilating elements of that approach. In these last two respects, Obama has so far been unsuccessful.

Reagan left office only slightly more popular than Obama is now. But Reagan also left his party holding more seats than it held when he was elected. The reverse is true of Obama, at every level of government. The public was also much happier with the state of the country when Reagan left office than it is now — although that measure of public opinion may say as much about growing polarization over the last few decades as about Obama’s performance.

The most important difference in their political records is that Reagan was followed in office by an ally while Obama will not be. George H. W. Bush ran for Reagan’s third term in 1988 and won a decisive victory. In this way he showed that Reaganism’s electoral success was not dependent on the surpassing political talent of Reagan himself. If she had won, perhaps Hillary Clinton would have shown that the political trend lines Obama had identified could carry even someone who lacked a trace of his charisma to victory.

But she did not win. The Democratic strategy of the Obama years has left the party locked out of power in the White House, the Senate, and the House at their end. A heavily urban and progressive coalition delivered presidential majorities twice, but its geography put the party at a structural disadvantage in Senate, House, and gubernatorial races. And the Democrats may have pushed their strategy too far even at the presidential level. If Clinton had replicated Obama’s 2012 performance among white Catholics or white Evangelicals or white working-class voters, she would have won the election. But her campaign was not geared to the sensibilities of any of these overlapping groups.

At no point in Obama’s presidency did his political success make Republicans consider assimilating some of his views into their philosophy, as Bill Clinton had done with Reaganism. Republicans are even less likely to make such an adjustment now.

The Democrats’ political defeats also imperil their policy achievements under Obama. It is not clear how much of Obamacare will survive. But it is clear enough already that Obama is no Reagan.

— Ramesh Ponnuru is a senior editor of National Review. This article appears in the January 23, 2017, issue of National Review.