A Road Map for Dealing With Campus Radicals

Jonathan Haidt is a member of one of America’s smallest fraternities — those who attempt to see beyond their own prejudices. In the left-leaning Chronicle of Higher Education, he notes that “intimidation is the new normal” on college campuses. The examples are well-known: The shout-down/shutdown of Heather Mac Donald at Claremont McKenna College; the riots sparked by Milo Yiannopoulos at Berkeley; the experience of Charles Murray at Middlebury College, where he and professor Allison Stanger were physically assaulted by a mob. Stanger was sent to the hospital with injuries. She said she feared for her life. Haidt writes:

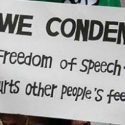

“We are witnessing the emergence of a dangerous new norm for responding to speakers who challenge campus orthodoxy. Anyone offended by the speaker can put out a call on Facebook to bring together students and locals, including ‘antifa’ (antifascist) and black-bloc activists who explicitly endorse the use of violence against racists and fascists. Because of flagrant ‘concept creep,’ however, almost anyone who is politically right of center can be labeled a racist or a fascist, and the promiscuous use of such labels is now part of the standard operating procedure.”

The only word I’d quarrel with is “new.” America’s campuses have been down this road — and worse — before.

At San Francisco State, it began with a fire in a dormitory. Hundreds of students awoke to a screaming alarm and rushed from their rooms in bathrobes as smoke and flames rose 30 feet from the roof. That no one was killed or injured was a miracle. The three-alarm fire left the social room of Merced Hall a smoking ruin. The year was 1967. The following year, the campus would be host (and I use that term advisedly) to the longest “student strike” in history. Dozens more fires were set, and radical students were able to shut down the entire campus for four months (there was even an attempted bombing). The college administration, in the face of law breaking, beatings and intimidation by radical students, backed off like cowards.

Dr. Thomas Sowell was a professor at Cornell University in 1969 when bands of armed black militant students forced visiting parents out of a campus building and then “occupied” it until their demands were met. Sowell wrote:

“The armed occupation of Willard Straight Hall was about reprimands — mere reprimands — received by some members of the Afro-American Society for previous disruptions and violence on campus. It was a demand for exemption from the authority of a duly constituted faculty-student disciplinary body that had dared to slap them on the wrist. Apparently existing de facto double standards were not enough, though such double standards were so well established that, when a parent, evicted from William Straight Hall by the students taking it over, phoned campus security, the first question he was asked was whether the students who had evicted him were white or black. When he said they were black, (he) ‘was told that there was nothing that could be done.'”

At Columbia University, students took faculty members hostage, occupied the office of the university president (David Shapiro was photographed smoking a cigar in the president’s chair) and took control of Hamilton Hall. Radicals shut down the entire campus and then battled the police, with one student permanently disabling a police officer by breaking his back when he leaped onto him from a second story window. And yet the administration and large numbers of faculty, rather than denounce the student thugs, praised and flattered them. University presidents from Yale (Kingman Brewster), Columbia (Grayson Kirk) and Cornell (James Perkins), among countless others, responded with pusillanimity to the radicals’ absurd demands and tactics.

But not at San Francisco State. Two presidents in quick succession had resigned rather than confront the students who were disrupting campus and committing violent crimes. And then came a third. A seemingly unprepossessing professor of semantics named S. I. Hayakawa was appointed acting president. As the radicals were chanting, drum beating and refusing to disperse, he jumped up on one of the sound trucks and pulled the plug on their speakers.

Instantly, he became a national hero, a celebrity status he was able to parlay into a seat in the U.S. Senate from California.

Hayakawa had no trouble rejecting the cant and cowardice all around him. Asked why, being of Japanese extraction, he didn’t side with minorities, he said he certainly did, but the radical activists did not speak for the majority of blacks or anyone else. They were media creations, he said, adding that TV news suffers from an excess of “show business values.”

There’s an opportunity awaiting someone, anyone, on today’s campuses, too. Stand up to the social-justice warriors, tell the truth, and you may find yourself a household name.