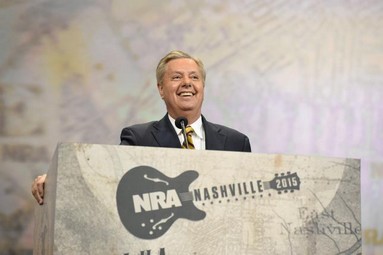

The Two Issues That Would Bedevil Lindsey Graham’s Campaign

Lindsey Graham once said his road to Congress ran through a coronary clinic because it involved so many South Carolina barbecues. Today, as a senator, he thinks he sees a path to the Republican presidential nomination. He has many strengths but two substantial problems.

Two clarifying issues efficiently reveal who actually is conservative and underscore two of Hillary Clinton’s vulnerabilities. They are the U.S. attack on Libya and her attack on freedom of political speech.

Secretary of State Clinton helped initiate a protracted assassination attempt — eight months of chasing Moammar Gaddafi with fighter-bombers. This exercise in regime change succeeded in decapitating Libya’s government. It was, however, progressive imperialism, supposedly humanitarian muscularity untainted by any clear and substantial U.S. national interest. Hence its appeal to a liberal administration, which neglected to ask the question conservatives have learned to ask before going abroad in search of monsters to destroy: “But then what?”

Now we know what. Libya is a failed state incubating radical Islamists.

In 2016, when Clinton is asked about her complicity in this calamity, she might say, “What difference, at this point, does it make?” Graham will be unable to press the point effectively. Eight years after the hard lessons of Iraq, he, too, supported violent regime change in Libya. His primary regret was that insufficient U.S. force was employed. In a joint statement with Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), Graham said: “Americans can be proud of the role our country” played, except for “the failure of the United States to employ the full weight of our air power.”

Graham did urge taking responsibility for the aftermath: “Let’s get on the ground and help the Libyan people establish a democracy.” Democracy’s prerequisites were, however, as lacking there as they were in Iraq, where we should have learned the perils of “nation-building,” and how discordant that project is with all conservative precepts.

Clinton promises to vastly expand the power of the political class to regulate campaign speech about itself, “even if that takes a constitutional amendment.” Graham is a better lawyer than Clinton but not clearly a better friend of the First Amendment. He knows it would be necessary to amend this amendment in order to overturn the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision, which he, like she, dislikes.

Citizens United upheld the right of corporations (in practice, almost entirely incorporated, nonprofit advocacy groups) and unions to unlimited spending for issue advocacy independent of candidates’ campaigns. The court simply reasoned that Americans do not forfeit their First Amendment rights when they join together to magnify their political speech.

Clinton’s aspiration to make the Bill of Rights less restraining on government and less protective of individuals would be accomplished by empowering Congress to legislate what it considers reasonable restrictions on contributions to finance the dissemination of political speech. The Post reports that, in New Hampshire recently, Graham “called for a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United.”

Challenged about this, he says he might consider instead undoing the damage he, his friend McCain and other “reformers” have done. Removing limits on contributions to parties (with immediate disclosure on the Internet) would divert the flow of money from super PACs back to the parties, where it once went. Parties should then be able to make unlimited expenditures for, and coordinate with, their candidates, which present law severely restricts. This would make parties more robust and accountable, and campaign political financing more transparent.

Super PACs, which Graham regrets as strongly as he needs and desires the backing of one, have been summoned into existence by limits on contributions to candidates and parties. These limits have diverted money into the super PACs that must not “coordinate” with candidates.

The infancy of super PACs is, Graham says, over. “They are full-blown teenagers” who in this cycle could, he thinks, produce a brokered nominating convention. A super PAC devoted to helping a particular candidate can “create viability beyond winning.” Usually, he says, candidacies are ended by a scarcity of money or a surfeit of embarrassment, or both. Suppose, however, that super PACs enable, say, five 2016 candidates to survive until July, losing often but winning here and there, particularly in states that allocate their delegates not winner-take-all but proportionally. Suppose the five reach the convention with a combined total of delegates larger than the 1,236 (this might change) needed for a nominating majority. What fun.

To reach a rendezvous with Clinton in the autumn of 2016, Graham must play by the rules we have. Win or lose, he is too intelligent to join her in proposing slapdash constitutional vandalism.