Muslim Americans responded with a mix of frustration, exasperation and anger to what many see as a growing wave of Islamophobia fueled by two of the Republican Party’s most popular presidential candidates, Donald Trump and Ben Carson.

At the Islamic Institute of Orange County, which houses a mosque and a school in Anaheim, in southern California, tensions were already mounting since a group of white men screamed at mothers and children arriving at the center on this year’s anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, calling them cowards who did not belong in America.

Many of the country’s 2.8 million Muslims say such tensions could become uglier during a presidential race that they fear is already tapping a vein of anger and bigotry.

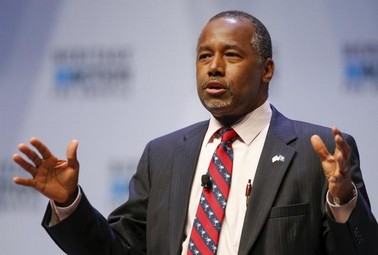

“It’s pretty troubling that someone running for president would make those claims,” Zuhair Shaath, Palestinian-American, said of Carson, a retired neurosurgeon who on Sunday said Muslims were unfit for the presidency of the United States.

Carson’s campaign defended his comments on Monday, saying he was not suggesting a Muslim should be barred from running for president. But his campaign said he would not advocate for that person becoming a leader and would not support it.

The remarks by Carson, who is near the top of opinion polls for the crowded field of Republican candidates for the 2016 election, followed billionaire Trump’s failure to challenge comments made on Friday by a supporter who labeled U.S. President Barack Obama a Muslim.

Trump later clarified his silence, saying he was not obligated to correct an audience member and that “the bigger issue is that Obama is waging a war against Christians in this country. Christians need support in this country. Their religious liberties are at stake.”

Some Muslims say they fear that the remarks could strengthen the appeal of Carson and Trump, who have cast themselves as non-politicians in a race in which blunt comments laced with misogyny and xenophobia have done little to derail the popularity of Trump, who is leading in opinion polls of likely Republican voters.

The comments also come after a 14-year-old Muslim boy from Texas was taken away in handcuffs last week for bringing to his Dallas-area school a homemade clock that staff mistook for a bomb. Ahmed Mohamed’s arrest sparked allegations of racial profiling and turned his school into an object of online outrage that culminated with Obama inviting Mohamed to the White House.

Nihad Awad, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, called on Carson to “withdraw from the presidential race because he is unfit to lead, because his views are inconsistent with the United States Constitution.”

In an Anaheim neighborhood known as “Little Arabia”, Abdallah Soueidan said the comments will inevitably cause trouble. “They are stirring things up,” said Soueidan, 57, who moved from Lebanon 37 years ago.

His 18-year-old son, Radwan – a college volleyball player in jeans and T-shirt – said he reads hate-filled anti-Muslim screeds online all the time. But, referring to Carson, he said: “I don’t know how a presidential candidate could say a thing like that. It doesn’t sound American at all.”

“WE ARE ALSO VOTERS”

While the U.S. Constitution forbids religious tests for those seeking public office, religion and presidential politics have long been a combustible mix.

In 2007, as Republican Mitt Romney campaigned for his party’s nomination, he faced fears among Evangelical Christians over his Mormon faith. In 1960, John F. Kennedy stressed the separation of church and state while campaigning to become the country’s first Roman Catholic president.

Aicha Fokar, 20, said Carson’s comments perpetuated “a really sick stereotype that’s been kind of embedding itself in the American culture.”

“It discourages young Muslims from standing up for their rights or for being proud about their faith,” said the student n Lubbock, Texas. “Everyone’s just trying to say things to get as many votes. I don’t think they understand what happens to us.

They don’t understand that we are also voters.”

In Dearborn, a Detroit suburb home to the country’s largest Muslim population, Marshal Shameri said Trump should have done more to dispel misconceptions of Islam. But he did not view the comments as an attack on his faith.

“As a candidate, as a businessman, as a man who is running for president, he should have been much, much sharper and clearer in his response and he wasn’t,” said Shameri, originally from Iraq.

Anti-Muslim tensions have been on display in another Detroit suburb, Sterling Heights, where city officials this month denied an Islamic group’s request to develop a mosque in a residential neighborhood. The mosque’s backers faced protests and filed a petition on Monday with the U.S. Department of Justice, seeking an investigation into whether their civil rights were violated.

In Kentucky, tensions flared last week when vandals defaced a mosque by spray-painting in bright red the words “Moslems - Leave the Jews Alone,” “This is for France” and “Nazis Speak Arabic”. Waheed Ahmad, president of the Louisville Islamic Center, played down the vandalism, blaming it on “a bunch of little rascals” who “got drunk or something”.

At Texas Tech University, Saba Nafees, 23, saw some irony in Carson’s comments.

“What is being portrayed in the media is extremism,” she said. “That’s what Islam is mistaken for, even though it’s not.”